You guys have a ton of articles.

This statement about Footballguys is a blessing but it can feel like a curse. Our staff delivers insights that change seasons for the better yet realistically, no fantasy owner has the time to read everything we publish in a week.

If this describes you, let me be your scout. Here are five insights from Footballguys articles that I find compelling for the weekend ahead. I'll share what should help you this week, touch on the long-term outlook, and sometimes offer a counterargument.

1. The New Reality: Contending Roster Management

Chad Parsons navigates the ever-changing landscape of dynasty leagues in his weekly Footballguys article. Parsons drops a strategic gem for your benefit in this week's piece on midseason trade ideas to bolster a playoff-caliber roster: Acquire older quarterbacks from non-contending teams for your stretch-run.

The general idea behind trading as a contending dynasty team is two-fold - acquiring production for the current year but also making dynasty trades which look at multiple seasons to aid a team, not a redraft-centric approach of buying a month or two of impact. The natural win-win trade for contending teams is targeting the non-contenders by offering rookie picks and/or hopeful producers and young players for 2020 and beyond.

*All listed trades have been executed in dynasty trades in the past week and are the type of construction recommended to contending dynasty teams*

QUARTERBACKS

Seeking older players from a non-contending team is a tried and true trade strategy for target production. With the NFL rules shift, dynasty GMs should be less concerned with age at quarterback than ever before. Brady is QB7 in terms of aWORP/G (Adjusted Wins Over Replacement Player) through Week 5 with three high impact performances. Ryan is QB5 and Rivers at QB12. Here are some recent trades involving these targets:

- Brady for 21 2nd

- Brady for 20 3rd

- Brady for Josh Oliver, 20 3rd

- Brady, 20 1st for Deshaun Watson

- Ryan for Drew Lock, 20 2nd

- Ryan for Kenny Golladay, 20 2nd (Superflex)

- Ryan for 20 2nd

- Ryan, Le'Veon Bell for Cam Newton, Melvin Gordon III

- Rivers for Josh Rosen

- Rivers for 21 2nd

- Rivers for 20 3rd

- Rivers, Preston Williams for Will Dissly, Joe Flacco

Matt's Thoughts: Considering the influx of young quarterbacks, the idea that 2020's quarterback class is strong, and the ridiculous recent talk that Tom Brady is declining (more on declining players in a moment...) should give savvy dynasty players an opportunity to get a solid quarterback that help them down the stretch as Parson's describes. Read the rest of his article for players to target at other positions.

2. Roundtable: Adam Harstad's Research Into The Aging Cliff

Speaking of Brady, Sigmund Bloom asked me on Thursday night if I bought into Brady experiencing a decline in play. If you factor injuries to the offensive line and wide receiver corps, and the retirement Rob Gronkowski, then, yes, Brady has experienced a decline in efficiency between him and his teammates.

If you strictly look at the aspects of his game he can control, Brady is playing well. However, we're obsessed with pinpointing when a player's skills are declining. This week, I posed this question to our Footballguys Roundtable panel in relation to the productive play of Jason Witten, Delanie Walker, and Greg Olsen and Adam Harstad asked if he could share is thoughts on this topic.

Here's what followed:

Adam Harstad: There are very, very few questions that I feel uniquely qualified to answer, but "historical aging patterns especially as pertaining to the tight end position" is, oddly enough, one of them. I've actually written a lot of words that are directly relevant to this subject, so (hopefully) you'll forgive a bit of self-promotional backlinking.

First off, I believe that we tend to fundamentally misunderstand how aging works in the NFL. If you've been playing fantasy football for more than a minute you've undoubtedly seen countless examples of "age curves", graphs that average production by every player at every age to show when each position "peaks" and "declines". According to these curves, for example, running backs are in their prime at age 25 and 26 and then start declining quickly from there. Here's a phenomenal example from good friend and talented analyst Chase Stuart using one of the cleverer approaches I've seen.

The problem though is these approaches suffer from something called the Ecological Fallacy, which is the idea that things that are true about groups in the aggregate are not necessarily true about the individuals that actually comprise that group.

Indeed, I used a similar approach of comparing running back performance from one year to the next, but I bucketed all backs into players who maintained their previous level of performance or even improved, players who declined by some reasonable amount, and players who essentially fell completely from relevance overnight. And older players were actually not any more likely to exhibit small declines than their younger peers (the yellow line below), but they were substantially more likely to suddenly implode entirely (red line).

Because implosion risk increases with age, when we average all running backs together we get a nice pretty age curve. Because moderate declines don't become more common with age, though, careers are very rarely curve-shaped. Instead, we tend to see players cruising along at a set level of performance until they suddenly and unexpectedly fall off the map entirely.

An aging curve model suggests that players should typically be worse in their last year than they were in their second-to-last year. In other words, as they get older their play declines. This intuitively makes sense.

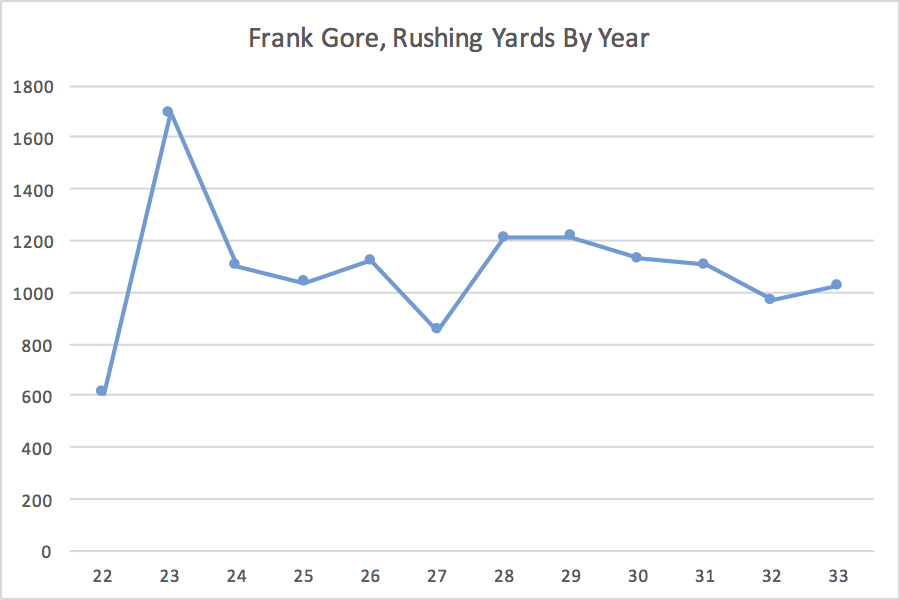

But if you look at the last two fantasy-relevant seasons from top 100 fantasy RBs and WRs from 1984-2014, you find that half of them were actually better in their last fantasy-relevant season than they were in their second-to-last season, which is exactly what you'd expect if improvement and decline were essentially random processes until the final and inevitable end.In 2017, Chase noted that "Frank Gore [wasn't] aging", using this chart to make the point:

I'd contend instead that Frank Gore is aging exactly how players tend to age-- that is to say, he's basically maintaining his set level of performance until at some point he hits a sudden and dramatic decline. Players are who they are until suddenly they aren't anymore. The only unique thing about Gore isn't the pattern of his career, it's how long he's managed to stave off the end.

Because of this, I'd also be wary of Dan's takeaway that "age-based regression does not hit tight ends nearly as hard as it does wide receiver and running backs". It's possible that this is the case. It's also possible that the recent trend of tight ends lasting longer is just statistical noise.

Indeed, I wrote about this exact phenomenon last season, noting that contrary to popular belief, NFL careers at most positions were not getting longer. (To use one dramatic example: from 1997 to 2000 there were seven double-digit sack seasons by a player 36 years or older. In eighteen years since there has only been one more. Similar patterns hold at wide receiver, offensive line, and even among placekickers and punters.)

At the one position where careers seemingly were getting longer (quarterback), it was more a result of random fluctuations in incoming talent than anything else. It's not that great quarterbacks were playing longer than they had in the past, it's that we had an unusually large number of great quarterbacks enter the league at the same time, which fifteen years later left us with an unusually large number of old quarterbacks at the same time.

There's also an element of selective memory at play here. The list of the most valuable fantasy tight-ends of the last decade includes the likes of Tony Gonzalez (whose last TE1 season came at age 37), Antonio Gates (36), Jason Witten (35), and Delanie Walker (33). It also includes Jimmy Graham (31), Rob Gronkowski (29), and Jordan Reed (26).

And if you want to dismiss Gronkowski and Reed because of their injury histories, remember that Greg Olsen-- one of the players being held up as proof that old tight ends can still play-- hasn't had a TE1 season since age 31. He's missed 16 games over the last two years, and in the games he did play he averaged just 30 yards, down from 66 yards from ages 29-31.

Had Olsen failed to make it back, we could easily dismiss him, too, as someone who didn't age so much as he succumbed to injury. Since he did make it back, we hold him up as proof that tight ends can continue playing well as they age. This is how insidiously selection bias works.

The best way to combat selection bias is with large samples based on objective criteria. I happen to have a list of the most valuable fantasy tight ends since 1985, and the top 20 includes Keith Jackson (last top-12 season at age 31), Ben Coates (29), Brent Jones (32), Steve Jordan (32), Jay Novacek (33), Jeremy Shockey (27), Mark Bavaro (30), Eric Green (30), Dallas Clark (30), Frank Wycheck (30), Todd Heap (26), and Kellen Winslow Jr. (27). Indeed, historically tight ends have tended to fall off earlier than wide receivers.

Maybe you don't think Frank Wycheck is really comparable to someone like Greg Olsen, but again, this is selection bias; Wycheck made pro bowls at ages 27, 28, and 29, and was a top-5 fantasy tight end for six consecutive seasons from age 25 to age 30. The reason we don't think he's comparable is because he fell off so young.

Perhaps the league has trended more towards using tight ends like receivers and we should expect the positions to age more comparably going forward, though there's little reason to expect tight ends to last longer than their more-heralded receiving peers. And I also don't know if I believe today's tight ends are behaving more like wide receivers than, say, Kellen Winslow Sr. (30) or Todd Christensen (31), who led the NFL in receptions four times in seven years from 1980 through 1986.

In the past, I've attempted to create "mortality tables" for each fantasy position based on how frequently historical players have "survived" at any given age vs. how frequently they have faced the sudden and inevitable decline. To get around the problem of changing usage at the tight end position (and the astronomically small sample of true receiving weapons over the years), I used a blended approach that compared modern tight ends to a sample that included both tight ends and wide receivers.

Now, as this pertains to tight ends Olsen, Witten, and Walker: because they are older, we should assume heading into this year that they were at heightened risk of a dramatic decline in their quality of play. But absent that sudden and dramatic decline, there's little reason to believe that they should have been noticeably less effective than they were the last time we saw them. And indeed, it looks like all three players have managed to outrun Father Time for at least one more season. Given their strong starts, I don't think any of the three are at any heightened risk of disappointing the rest of the way than any other comparably productive tight end.

At the same time, I feel hesitant to suggest (as the question implies) that it's unwise to discount aging players at tight end. I think they genuinely are riskier assets than their younger peers. We know with certainty that the end comes for everyone, and the older a player becomes the more likely it is that this year is the year they are no longer who they once were. The fact that this year wasn't the year for Olsen, Witten, or Walker doesn't change that fact.

I'd compare player aging not to a smooth curve, but to a series of weighted coin flips. Imagine that every player has made a deal with the devil. Before the season, they flip a coin. If the coin comes up heads they survive another year unscathed. If the coin comes up tails they have reached the end of the road. Perhaps they continue on as a shell of their former selves, perhaps they suffer a career-ending injury or suddenly retire, but one way or another they are no longer who they once were.

Every year that coin becomes weighted more and more toward tails, but just like anything involving coin flips, there's nothing fundamentally preventing someone like Jerry Rice from flipping heads every year into his 40s. Nor is there anything preventing Andre Johnson from flipping tails at 33, or Herman Moore at 30, or Dez Bryant at 27, or David Boston at 25. Each of these events differs in terms of relative likelihood, but again, assuming probabilistic statements that are true at the group level will apply to individual members of that group is how we got into this mess in the first place.

So to sum up: age is a serious concern for tight ends (and for all players at every position), not because it tends to make players a little bit worse, but because it tends to make players a little bit more likely to become a lot worse all at once. But if we can see that a player hasn't become a lot worse all of a sudden, then I don't know that knowing their age adds any further explanatory power.

Matt's Thoughts: For those keeping score at home, remember..."Age is a serious concern for tight ends (and for all players at every position), not because it tends to make players a little bit worse, but because it tends to make players a little bit more likely to become a lot worse all at once. But if we can see that a player hasn't become a lot worse all of a sudden, then I don't know that knowing their age adds any further explanatory power."

In other words, it will be a lot more obvious that Tom Brady is in decline than the speculation that talking heads are saying on shows that air during the same time of day as soap operas.

3. TrendSpotting: Atlanta's Defense

As mentioned in my Top 10 column on Monday, Atlanta defense is the fantasy gift that keeps on giving. Ryan Hester examines from a data perspective in his popular Trendspotting feature.

Arizona (O) vs. Atlanta (D)

Photos provided by Imagn Images